|

The question mark, a seemingly simple punctuation mark, holds the power to transform a sentence into a query, eliciting curiosity and engagement. When it comes to rhetorical questions, however, the rules become a bit more nuanced. In this guide, we'll delve into the correct use of question marks in relation to rhetorical questions, unraveling the art of crafting compelling inquiries that captivate your audience.

Rhetorical questions are a rhetorical device used to make a point rather than to seek an answer. They are crafted to provoke thought, emphasize a statement, or engage the audience in a conversation. Unlike direct questions, which anticipate a response, rhetorical questions are designed to be answered implicitly through the context or the speaker's intended message. 1. Omitting the Question Mark: One common practice in using rhetorical questions is to omit the question mark altogether. This technique is effective when the statement is clearly intended as a rhetorical question and adding a question mark might seem redundant. For example: Who could resist the allure of a perfect sunset. Here, the absence of a question mark implies that the question is rhetorical, leaving a subtle invitation for the reader to reflect on the beauty of a perfect sunset without explicitly seeking an answer. 2. Using a Question Mark for Emphasis: While omitting the question mark is a valid approach, there are instances where adding one can enhance the rhetorical impact. By including a question mark, you emphasize the rhetorical nature of the question, creating a deliberate pause for reflection. Consider the following example: Could there be a more enchanting moment than this? Here, the question mark adds emphasis, inviting the reader to pause and contemplate the rhetorical nature of the question. It accentuates the sentiment being conveyed, making the statement more impactful. 3. Context Matters: In the realm of rhetorical questions, context is key. The effectiveness of a rhetorical question depends on the surrounding content, tone, and the writer's intent. Before deciding whether to include or omit a question mark, consider the overall message you want to convey and how the rhetorical question fits into the broader narrative. Conclusion: Mastering the correct use of question marks in relation to rhetorical questions is an art that requires an understanding of language nuances and the intended impact on your audience. Whether you choose to omit the question mark for subtlety or include it for emphasis, the key is to maintain clarity and coherence in your communication. By navigating the delicate balance between punctuation and rhetoric, you can craft questions that not only engage your readers but also leave a lasting impression.

0 Comments

The English language is known for its quirks and idiosyncrasies, and one intriguing phenomenon is the presence of silent letters. Among these silent letters, the silent "p" at the beginning of certain words stands out as particularly enigmatic. In this blog post, we will delve into the fascinating world of silent "p" words, exploring their origins, linguistic evolution, and cultural influences. So, let's embark on a journey to unravel the mysteries of these peculiar linguistic anomalies.

I. The Historical Heritage: Etymological Origins Silent "p" words often trace their origins back to ancient Greek or Latin. The letter "p" was pronounced in the original source language, but its pronunciation changed over time. Examples: pneumonia, psychology, pterodactyl, pneumatic. II. The Influence of French: The Norman Conquest The defeat of the English at the hands of their neighbours across the English Channel brought French elements into the English language. French words with silent "p" sounds infiltrated the lexicon during this period. Examples: receipt, pneumonia (derived from French pneumatique), pterodactyl (from Greek via French). III. Phonological Shifts: Sound Changes and Phonetic Evolution Pronunciation shifts in English led to the omission of certain sounds, including the silent "p." These changes were gradual and varied across regions and dialects. Examples: pneumonia (/njuːˈmoʊniə/ to /nəˈmoʊniə/), psychology (/saɪˈkɒlədʒi/ to /saɪˈkɑːlədʒi/). IV. Sociolinguistic Factors: Prestige and Euphony Silent letters were often associated with prestige and the educated classes. Pronouncing silent letters was seen as an indication of refined speech. Euphony, or pleasantness of sound, played a role in the preservation of silent letters. Examples: pneumonia, ptarmigan (pronounced "tarmigan"). Conclusion: The presence of silent "p" words in the English language adds a layer of complexity and intrigue to our linguistic landscape. Through a combination of historical factors, phonological shifts, and sociolinguistic influences, these silent letters have become an integral part of our vocabulary. The etymological origins rooted in ancient languages, the impact of the Norman Conquest, and the evolving pronunciation patterns have all contributed to the silent "p" phenomenon we observe today. By understanding the fascinating backstory behind these words, we gain a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of language and its dynamic nature. So, the next time you encounter a word like "pneumonia" or "psychology" with a silent "p," you can marvel at the linguistic journey that brought it to its current form. References:

A proofreader's guide to grammarSo, as promised in last week’s blog post, I’m going to start looking at some of the ‘tricksier’ aspects of English grammar and providing a proofreader’s perspective on usage and abusage. Before I start on the elements of grammar itself, I wanted to use this first post to explain what I mean by ‘a proofreader’s perspective’. Surely it makes no difference whether you’re the originator or proofreader of a sentence. Surely, the same rules apply. Strictly speaking, yes, the same rules apply. But there are qualitative decisions a writer makes with which a proofreader needn’t concern themselves. Remember, you’re a proofreader not an editor. You’re not asking yourself whether or not a sentence is good, you’re checking to make sure it’s correct. Let’s take a look at the semicolon (I’m going to be talking about this in more detail next week) to illustrate what I mean. So, a writer is trying to describe the moment in her novel when a particular character realises she has become invisible. She writes: Melissa couldn’t see herself in the mirror because she was invisible. She then deletes that sentence and writes: Melissa couldn’t see herself in the mirror. She was invisible. She then deletes that sentence and writes: Melissa couldn’t see herself in the mirror; she was invisible. Happy with this third permutation, she goes on to describe Melissa’s adventures in invisibility. None of these options is incorrect. The writer’s use of the semicolon in the third version is fine; the semicolon can be used in place of a conjunction. But you might have an opinion on which version is qualitatively better. Me, I like the second option. I think it has more punch. As a proofreader, my opinion on such matters isn’t relevant. I’ve got a job of work to do. I’m looking for errors. That’s what my client is paying me for. That’s what your client will be paying you for. If you’ve picked up The No-Nonsense Proofreading Course, followed its instruction and taken its advice, you’ll be charging your customer $35 per hour to find errors in their work. You might even be charging more if you’re proofreading in a niche area: science, medicine, law. You might have lots of clients and a stack of proofreading that’s going to keep you in new shoes and good food for the next three months. You haven’t got time to be getting into a discussion with a writer over whether or not a period would serve better than a semicolon in a particular instance. Don’t get me wrong, if your ambition is to become an editor, proofreading offers a very effective way in. In fact, Chapter 8 of The No-Nonsense Proofreading Course deals, in part, with that transition. But on this website, we really want to focus on how to proofread, how to become a proofreader and how to create and develop your proofreading career or business. Believe me, that’s more than enough to be getting on with. Let’s go back to our writer, and the adventures of the now invisible Melissa. Our writer types: Melissa raises a hand, holds it inches from her face and sees nothing. She deletes this and decides to go with: Melissa raises a hand to her face; and sees nothing. Now, as a proofreader, you have grounds to take issue. The writer has used a semicolon and a conjunction, which is redundant. You only need one or the other. So, put your red pen to work and mark it up. The writer might come back and say the usage was intentional, that she was trying to create a ‘beat’. That’s her call. In my opinion, a period would serve better in trying to achieve that effect: Melissa raises a hand to her face. And sees nothing. But it’s her call.

The fact remains, you were right to draw attention to this inaccurate use of a semicolon. You were doing your job as a proofreader and you were doing it well. In a nutshell, as a proofreader you’re concerned with wrong and right, not good-better-best. So, that’s what I mean when I say I’ll be looking at grammar usage and abusage from a proofreader’s perspective. See you next time, when I’ll be looking at that little winking-eye emoji in a little more depth. Until then, Mike Spelling errors are always embarrassing. Just how embarrassing depends upon the nature and location of that spelling mistake. A spelling mistake on a large sign is a pretty big deal. When that sign is advertising the services of a school, it's an even bigger deal. And when the word that has been incorrectly spelled is 'grammar'... well, that's about as embarrassing as it gets.

But that's precisely the mistake that an absence of effective proofreading resulted in for a Christian Brothers' school in Omagh (see picture) when the word 'grammar' was spelled 'grammer'. Oops. Not only were those responsible exposed to a little local ridicule, they were also, thanks to the wonders of social media, subjected to a fair amount of international mockery. Homophones (words with the same sound but a different spelling and meaning) can be the proofreader's worst enemy. Here's a comprehensive list of homophones. I can't claim the credit for compiling the list, by the way, as it's pretty much all over the internet. To the person who put all the work in, I offer my gratitude.

Here's the list (print it out and keep it close at hand): 1. accessary, accessory 2. ad, add 3. ail, ale 4. air, heir 5. aisle, I'll, isle 6. all, awl 7. allowed, aloud 8. alms, arms 9. altar, alter 10. arc, ark 11. aren't, aunt 12. ate, eight 13. auger, augur 14. auk, orc 15. aural, oral 16. away, aweigh 17. awe, oar, or, ore 18. axel, axle 19. aye, eye, I 20. bail, bale 21. bait, bate 22. baize, bays 23. bald, bawled 24. ball, bawl 25. band, banned 26. bard, barred 27. bare, bear 28. bark, barque 29. baron, barren 30. base, bass 31. bay, bey 32. bazaar, bizarre 33. be, bee 34. beach, beech 35. bean, been 36. beat, beet 37. beau, bow 38. beer, bier 39. bel, bell, belle 40. berry, bury 41. berth, birth 42. bight, bite, byte 43. billed, build 44. bitten, bittern 45. blew, blue 46. bloc, block 47. boar, bore 48. board, bored 49. boarder, border 50. bold, bowled 51. boos, booze 52. born, borne 53. bough, bow 54. boy, buoy 55. brae, bray 56. braid, brayed 57. braise, brays, braze 58. brake, break 59. bread, bred 60. brews, bruise 61. bridal, bridle 62. broach, brooch 63. bur, burr 64. but, butt 65. buy, by, bye 66. buyer, byre 67. calendar, calender 68. call, caul 69. canvas, canvass 70. cast, caste 71. caster, castor 72. caught, court 73. caw, core, corps 74. cede, seed 75. ceiling, sealing 76. cell, sell 77. censer, censor, sensor 78. cent, scent, sent 79. cereal, serial 80. cheap, cheep 81. check, cheque 82. choir, quire 83. chord, cord 84. cite, sight, site 85. clack, claque 86. clew, clue 87. climb, clime 88. close, cloze 89. coal, kohl 90. coarse, course 91. coign, coin 92. colonel, kernel 93. complacent, complaisant 94. complement, compliment 95. coo, coup 96. cops, copse 97. council, counsel 98. cousin, cozen 99. creak, creek 100. crews, cruise 101. cue, kyu, queue 102. curb, kerb 103. currant, current 104. cymbol, symbol 105. dam, damn 106. days, daze 107. dear, deer 108. descent, dissent 109. desert, dessert 110. deviser, divisor 111. dew, due 112. die, dye 113. discreet, discrete 114. doe, doh, dough 115. done, dun 116. douse, dowse 117. draft, draught 118. dual, duel 119. earn, urn 120. eery, eyrie 121. ewe, yew, you 122. faint, feint 123. fah, far 124. fair, fare 125. farther, father 126. fate, fête 127. faun, fawn 128. fay, fey 129. faze, phase 130. feat, feet 131. ferrule, ferule 132. few, phew 133. fie, phi 134. file, phial 135. find, fined 136. fir, fur 137. fizz, phiz 138. flair, flare 139. flaw, floor 140. flea, flee 141. flex, flecks 142. flew, flu, flue 143. floe, flow 144. flour, flower 145. foaled, fold 146. for, fore, four 147. foreword, forward 148. fort, fought 149. forth, fourth 150. foul, fowl 151. franc, frank 152. freeze, frieze 153. friar, fryer 154. furs, furze 155. gait, gate 156. galipot, gallipot 157. gallop, galop 158. gamble, gambol 159. gays, gaze 160. genes, jeans 161. gild, guild 162. gilt, guilt 163. giro, gyro 164. gnaw, nor 165. gneiss, nice 166. gorilla, guerilla 167. grate, great 168. greave, grieve 169. greys, graze 170. grisly, grizzly 171. groan, grown 172. guessed, guest 173. hail, hale 174. hair, hare 175. hall, haul 176. hangar, hanger 177. hart, heart 178. haw, hoar, whore 179. hay, hey 180. heal, heel, he'll 181. hear, here 182. heard, herd 183. he'd, heed 184. heroin, heroine 185. hew, hue 186. hi, high 187. higher, hire 188. him, hymn 189. ho, hoe 190. hoard, horde 191. hoarse, horse 192. holey, holy, wholly 193. hour, our 194. idle, idol 195. in, inn 196. indict, indite 197. it's, its 198. jewel, joule 199. key, quay 200. knave, nave 201. knead, need 202. knew, new 203. knight, night 204. knit, nit 205. knob, nob 206. knock, nock 207. knot, not 208. know, no 209. knows, nose 210. laager, lager 211. lac, lack 212. lade, laid 213. lain, lane 214. lam, lamb 215. laps, lapse 216. larva, lava 217. lase, laze 218. law, lore 219. lay, ley 220. lea, lee 221. leach, leech 222. lead, led 223. leak, leek 224. lean, lien 225. lessen, lesson 226. levee, levy 227. liar, lyre 228. licence, license 229. licker, liquor 230. lie, lye 231. lieu, loo 232. links, lynx 233. lo, low 234. load, lode 235. loan, lone 236. locks, lox 237. loop, loupe 238. loot, lute 239. made, maid 240. mail, male 241. main, mane 242. maize, maze 243. mall, maul 244. manna, manner 245. mantel, mantle 246. mare, mayor 247. mark, marque 248. marshal, martial 249. marten, martin 250. mask, masque 251. maw, more 252. me, mi 253. mean, mien 254. meat, meet, mete 255. medal, meddle 256. metal, mettle 257. meter, metre 258. might, mite 259. miner, minor, mynah 260. mind, mined 261. missed, mist 262. moat, mote 263. mode, mowed 264. moor, more 265. moose, mousse 266. morning, mourning 267. muscle, mussel 268. naval, navel 269. nay, neigh 270. nigh, nye 271. none, nun 272. od, odd 273. ode, owed 274. oh, owe 275. one, won 276. packed, pact 277. packs, pax 278. pail, pale 279. pain, pane 280. pair, pare, pear 281. palate, palette, pallet 282. pascal, paschal 283. paten, patten, pattern 284. pause, paws, pores, pours 285. pawn, porn 286. pea, pee 287. peace, piece 288. peak, peek, peke, pique 289. peal, peel 290. pearl, purl 291. pedal, peddle 292. peer, pier 293. pi, pie 294. pica, pika 295. place, plaice 296. plain, plane 297. pleas, please 298. plum, plumb 299. pole, poll 300. poof, pouffe 301. practice, practise 302. praise, prays, preys 303. principal, principle 304. profit, prophet 305. quarts, quartz 306. quean, queen 307. rain, reign, rein 308. raise, rays, raze 309. rap, wrap 310. raw, roar 311. read, reed 312. read, red 313. real, reel 314. reek, wreak 315. rest, wrest 316. retch, wretch 317. review, revue 318. rheum, room 319. right, rite, wright, write 320. ring, wring 321. road, rode 322. roe, row 323. role, roll 324. roo, roux, rue 325. rood, rude 326. root, route 327. rose, rows 328. rota, rotor 329. rote, wrote 330. rough, ruff 331. rouse, rows 332. rung, wrung 333. rye, wry 334. saver, savour 335. spade, spayed 336. sale, sail 337. sane, seine 338. satire, satyr 339. sauce, source 340. saw, soar, sore 341. scene, seen 342. scull, skull 343. sea, see 344. seam, seem 345. sear, seer, sere 346. seas, sees, seize 347. sew, so, sow 348. shake, sheikh 349. shear, sheer 350. shoe, shoo 351. sic, sick 352. side, sighed 353. sign, sine 354. sink, synch 355. slay, sleigh 356. sloe, slow 357. sole, soul 358. some, sum 359. son, sun 360. sort, sought 361. spa, spar 362. staid, stayed 363. stair, stare 364. stake, steak 365. stalk, stork 366. stationary, stationery 367. steal, steel 368. stile, style 369. storey, story 370. straight, strait 371. sweet, suite 372. swat, swot 373. tacks, tax 374. tale, tail 375. talk, torque 376. tare, tear 377. taught, taut, tort 378. te, tea, tee 379. team, teem 380. tear, tier 381. teas, tease 382. terce, terse 383. tern, turn 384. there, their, they're 385. threw, through 386. throes, throws 387. throne, thrown 388. thyme, time 389. tic, tick 390. tide, tied 391. tire, tyre 392. to, too, two 393. toad, toed, towed 394. told, tolled 395. tole, toll 396. ton, tun 397. tor, tore 398. tough, tuff 399. troop, troupe 400. tuba, tuber 401. vain, vane, vein 402. vale, veil 403. vial, vile 404. wail, wale, whale 405. wain, wane 406. waist, waste 407. wait, weight 408. waive, wave 409. wall, waul 410. war, wore 411. ware, wear, where 412. warn, worn 413. wart, wort 414. watt, what 415. wax, whacks 416. way, weigh, whey 417. we, wee, whee 418. weak, week 419. we'd, weed 420. weal, we'll, wheel 421. wean, ween 422. weather, whether 423. weaver, weever 424. weir, we're 425. were, whirr 426. wet, whet 427. wheald, wheeled 428. which, witch 429. whig, wig 430. while, wile 431. whine, wine 432. whirl, whorl 433. whirled, world 434. whit, wit 435. white, wight 436. who's, whose 437. woe, whoa 438. wood, would 439. yaw, yore, your, you're 440. yoke, yolk 441. you'll, yule Thanks, again, to the original creator. The period, or full stop, marks the end of a declarative sentence. As a sign it has several other uses which will appear in the paragraphs following.

Rules for the Use of the Period 1. At the end of every sentence unless interrogative or exclamatory. 2. After abbreviations. Nicknames, Sam, Tom, etc., are not regarded as abbreviations. The metric symbols are treated as abbreviations but the chemical symbols are not. M. (metre) and mg. (milligram) but Na Cl or CO Per cent is not regarded as an abbreviation. The names of book sizes (12mo 16mo) are not regarded as abbreviations. 4. The period is now generally omitted in display matter after: Running heads, Cut-in side-notes, Central head-lines, Box heads in tables, Signatures at the end of letters. 5. The period is omitted: After Roman numerals, even though they have the value of ordinals. After MS and similar symbols. In technical matter, after the recognized abbreviations for linguistic epochs. IE (Indo-European), MHG (Middle High German) After titles of well-known publications indicated by initials such as AAAPS (Annals of the American Academy of Political Science). 6. When a parenthesis forms the end of a declarative sentence the period is placed outside the parenthesis, as in the preceding example. A period is placed inside a parenthesis only in two cases. i. After an abbreviation. This was 50 years ago (i.e. 1860 A.D.) ii. At the end of an independent sentence lying entirely within the parenthesis. Lincoln was at the height of his powers in 1860 (He was elected to the presidency at this time.) 7. When a sentence ends with a quotation, the period always goes inside the quotation marks. I have just read DeVinne's "Practice of Typography." The same rule applies to the use of the other low marks, comma, semicolon, and colon, in connection with quotation marks. Unlike most rules of grammar and punctuation, this rule does not rest on a logical basis. It rests on purely typographic considerations, as the arrangement of points indicated by the rule gives a better looking line than can be secured by any other arrangement. Other Uses of the Period 1. The period is used as a decimal point. 2. The period is used in groups, separated by spaces, to indicate an ellipsis. He read as follows: "The gentleman said . . . he was there and saw . . . the act in question." Apologies. I got a couple of steps ahead of myself. In this post, Frederick W. Hamilton will be telling us all about the colon. After that, we’ll be looking at the full stop (or period) and then we’ll be tackling that innocuous-looking little dash. THE COLON The colon marks the place of transition in a long sentence consisting of many members and involving a logical turn of the thought. Both the colon and semicolon are much less used now than formerly. The present tendency is toward short, simple, clear sentences, with consequent little punctuation, and that of the open style. Such sentences need little or no aid to tell their story. Rules for the Use of the Colon 1. Before as, viz., that is, namely, etc., when these words introduce a series of particular terms in apposition with a general term. The American flag has three colours: namely, red, white, and blue. 2. Between two members of a sentence when one or both are made up of two or more clauses divided by semicolons. The Englishman was calm and self-possessed; his antagonist impulsive and self-confident: the Englishman was the product of a volunteer army of professional soldiers; his antagonist was the product of a drafted army of unwilling conscripts. 3. Before particular elements in a definite statement. Bad: He asked what caused the accident? Right: He asked, "What caused the accident?" Napoleon said to his army at the battle of the Pyramids: "Soldiers, forty centuries are looking down upon you." The duties of the superintendent are grouped under three heads: first, etc. 4. Before formal quotations. Write a short essay on the following topic: "What is wrong with our industrial system?" When the formal introduction is brief, a comma may be used. St. Paul said, "Bear ye one another's burdens." 5. After the formal salutatory phrase at the opening of a letter. My dear Sir: When the letter is informal use a comma. Dear John, 6. Between the chapter and verse in scriptural references. John xix: 22. 7. Between the city of publication and the name of the publisher in literary references. "The Practice of Typography." New York: Oswald Publishing Company. The colon has been similarly employed in the imprints on the title pages of books. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1880. DeVinne remarks upon this use of the colon that it is traditional and cannot be explained. The colon is sometimes used between the hours and minutes in indicating time, like: 11:42 a.m. DeVinne does not approve of this, though other authorities give it as the rule. It is probably better to use the period in spite of its use as a decimal point, which use was probably the motive for seeking something else to use in writing time indications. In railroad printing the hour is often separated from the minutes by a simple space without any punctuation. Welcome back. Here's part two of my serialisation of Frederick W. Hamilton's Punctuation. Today, it's the turn of the semicolon, probably the piece of punctuation that generates the most anxiety. But it's really pretty simple. Over to you, Frederick...

THE SEMICOLON The semicolon is used to denote a degree of separation greater than that indicated by the comma, but less than that indicated by the colon. It prevents the repetition of the comma and keeps apart the more important members of the sentence. The semicolon is generally used in long sentences, but may sometimes be properly used in short ones. Rules for the Use of the Semicolon 1. When the members of a compound sentence are complex or contain commas. Franklin, like many others, was a printer; but, unlike the others, he was student, statesman, and publicist as well. With ten per cent of this flour the bread acquired a slight flavor of rye; fifteen per cent gave it a dark color; a further addition made the baked crumb very hard. The meeting was composed of representatives from the following districts: Newton, 4 delegates, 2 substitutes; Dorchester, 6 delegates, 3 substitutes; Quincy, 8 delegates, 4 substitutes; Brookline, 10 delegates, 5 substitutes. 2. When the members of a compound sentence contain statements distinct, but not sufficiently distinct to be thrown into separate sentences. Sit thou a patient looker-on; Judge not the play before the play be done; Her plot has many changes; every day Speaks a new scene. The last act crowns the play. 3. When each of the members of a compound sentence makes a distinct statement and has some dependence on statements in the other member or members of the sentence. Wisdom hath builded her house; she hath hewn out her seven pillars; she hath killed her beasts; she hath mingled her wine; she hath furnished her table. Each member of this sentence is nearly complete. It is not quite a full and definite statement, but it is much more than a mere amplification such as we might get by leaving out she hath every time after the first. In the former case we should use periods. In the latter we should use commas. 4. A comma is ordinarily used between the clauses of a compound sentence that are connected by a simple conjunction, but a semicolon may be used between clauses connected by conjunctive adverbs. Compare the following examples: The play was neither edifying nor interesting to him, and he decided to change his plans. The play was neither edifying nor interesting to him; therefore he decided to change his plans. 5. To indicate the chapter references in scriptural citations. Matt. i: 5, 7, 9; v: 1-10; xiv: 3, 8, 27. The semicolon should always be put outside quotation marks unless it forms a part of the quotation itself. "Take care of the cents and the dollars will take care of themselves"; a very wise old saying. And that's it for the semicolon. Next, that innocent-looking, yet surprisingly tricksy piece of punctuation, the dash. I’ve made no secret of my surprise that many proofreading courses have the audacity to actually sell grammar instruction as part of their course content, when said instruction can be found elsewhere free of charge. So, rather than just talk about this free grammar instruction, I’m going to actually provide it, by serialising a couple of books over the next few weeks. I’m going to start with Frederick W. Hamilton’s 1920 book, Punctuation, the first chapter of which describes the uses and abuses of the comma.

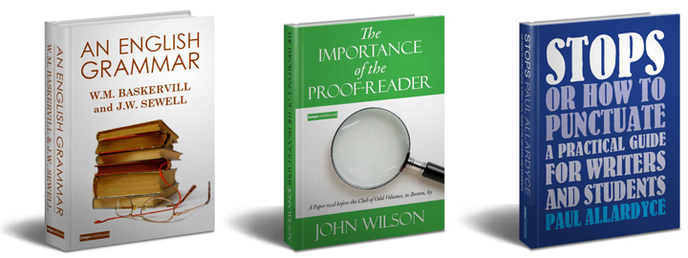

THE COMMA The comma is by far the most difficult of all the punctuation marks to use correctly. Usage varies greatly from time to time and among equally good writers and printers at the same time. Certain general rules may be stated and should be learned. Many cases, however, will arise in which the rules will be differently interpreted and differently applied by different people. The comma is the least degree of separation possible of indication in print. Its business is to define the particles and minor clauses of a sentence. A progressive tendency may be seen in the printing of English for centuries toward the elimination of commas, and the substitution of the comma for the semicolon and of the semicolon for the colon. Compare a page of the King James version of the Bible, especially in one of its earlier printings, with a page of serious discourse of to-day and the effects of the tendency will be easily seen. It is part of the general tendency toward greater simplicity of expression which has developed the clear and simple English of the best contemporary writers out of the involved and ornate style of the period of Queen Elizabeth. An ornate and involved style needs a good deal of punctuation to make it intelligible, while a simple and direct style needs but very little help. This progressive change in the need for punctuation and in the attitude of writers toward it accounts for the difference in usage and for the difficulty in fixing rules to cover all cases. The present attitude toward punctuation, especially the use of the comma, is one of aversion. The writer is always held to justification of the presence of a comma rather than of its absence. Nevertheless it is quite possible to go too far in the omission of commas in ordinary writing. It is quite possible to construct sentences in such a way as to avoid their use. The result is a harsh and awkward style, unwarranted by any necessity. Ordinary writing needs some use of commas to indicate the sense and to prevent ambiguity. Always remember that the real business of the comma is just that of helping the meaning of the words and of preventing ambiguity by showing clearly the separation and connection of words and phrases. If there is possibility of misunderstanding without a comma, put one in. If the words tell their story beyond possibility of misunderstanding without a comma, there is no reason for its use. This rule will serve as a fairly dependable guide in the absence of any well recognized rule for a particular case, or where doubt exists as to the application of a rule. Reversed, and usually in pairs, commas mark the beginning of a quotation. In numerical statements the comma separates Arabic figures by triplets in classes of hundreds: $5,276,492.72. The comma is placed between the words which it is intended to separate. When used in connection with quotation marks, it is always placed inside them. “Honesty is the best policy,” as the proverb says. Rules for the Use of the Comma 1. After each adjective or adverb in a series of two or more when not connected by conjunctions. He was a tall, thin, dark man. The rule holds when the last member of the series is preceded by a conjunction. He was tall, thin, and dark. The comma may be omitted when the words are combined into a single idea. A still hot day. An old black coat. 2. After each pair in a series of pairs of words or phrases not connected by conjunctions. Sink or swim, live or die, survive or perish, I give my hand and my heart to this vote. Formerly the master printer, his journeymen, even his apprentices, all lived in the same house. 3. To separate contrasted words. We rule by love, not by force. 4. Between two independent clauses connected by a conjunction. The press was out of order, but we managed to start it. 5. Before a conjunction when the word which preceded it is qualified by an expression which does not qualify the word which follows the conjunction. He quickly looked up, and spoke. 6. Between relative clauses which explain the antecedent, or which introduce a new thought. The type, which was badly worn, was not fit for the job. If the relative clause limits the meaning of the antecedent, but does not explain it and does not add a new thought, the comma is not used. He did only that which he was told to do. 7. To separate parenthetical or intermediate expressions from the context. The school, you may be glad to know, is very successful. The books, which I have read, are returned with gratitude. He was pleased, I suppose, with his work. If the connection of such expressions is so close as to form one connected idea the comma is not used. The press nearest the south window is out of order. If the connection of such expressions is remote, parentheses are used. The Committee (appointed under vote of April 10, 1909) organized and proceeded with business. 8. To separate the co-ordinate clauses of compound sentences if such clauses are simple in construction and closely related. He was kind, not indulgent, to his men; firm, but just, in discipline; courteous, but not familiar, to all. 9. To separate quotations, or similar brief expressions from the preceding part of the sentence. Cæsar reported to the Senate, “I came, I saw, I conquered.” The question is, What shall we do next? 10. To indicate the omission of the verb in compound sentences having a common verb in several clauses. One man glories in his strength, another in his wealth, another in his learning. 11. To separate phrases containing the case absolute from the rest of the sentence. The form having been locked up, a proof was taken. 12. Between words or phrases in apposition to each other. I refer to DeVinne, the great authority on Printing. The comma is omitted when such an apposition is used as a single phrase or a compound name. The poet Longfellow was born in Portland. The word patriotic is now in extensive use. 13. After phrases and clauses which are placed at the beginning of a sentence by inversion. Worn out by hard wear, the type at last became unfit for use. Ever since, he has been fond of celery. The comma is omitted if the phrase thus used is very short. Of success there could be no doubt. 14. Introductory phrases beginning with if, when, wherever,whenever, and the like should generally be separated from the rest of the sentence by a comma, even when the statement may appear to be direct. When a plain query has not been answered, it is best to follow copy. If the copy is hard to read, the compositor will set but few pages. 15. To separate introductory words and phrases and independent adverbs from the rest of the sentence. Now, what are you going to do there? I think, also, Franklin owed much of his success to his strong common sense. This idea, however, had already been grasped by others. Of course the comma is not used when these adverbs are used in the ordinary way. They also serve who only stand and wait. This must be done, however contrary to our inclinations. 16. To separate words or phrases of direct address from the context. I submit, gentlemen, to your judgment. From today, my son, your future is in your own hands. 17. Between the name of a person and his title or degree. Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States. Charles W. Eliot, LL.D. 18. Before the word of connecting a proper name with residence or position. Senator Lodge, of Massachusetts. Elihu B. Root, Senator from New York. 19. After the salutatory phrase at the beginning of a letter, when informal. Dear John, When the salutation is formal a colon should be used. My dear Mr. Smith: 20. To separate the closing salutation of a formal letter from the rest of the sentence of which it forms a part. Soliciting your continued patronage, I am, Very sincerely yours, John W. Smith. 21. To separate two numbers. January 31, 1915. By the end of 1914, 7062 had been built. 22. To indicate an ellipsis. Subscription for the course, one dollar. Exceptions to this rule are made in very brief sentences, especially in advertisements: Tickets 25 cents. Price one dollar. The foregoing rules for the use of the comma have been compiled from those given by a considerable number of authorities. Further examination of authorities would probably have added to the number and to the complexity of these rules. No two sets of rules which have come under the writer’s observation are alike. Positive disagreements in modern treatises on the subject are few. The whole matter, however, turns so much on the use made of certain general principles and the field is so vast that different writers vary greatly in their statements and even in their ideas of what ought to be stated. It is very difficult to strike the right mean between a set of rules too fragmentary and too incomplete for any real guidance and a set of rules too long to be remembered and used. After all possible has been done to indicate the best usage it remains true that the writer or the printer must, in the last resort, depend very largely on himself for the proper application of certain principles. The compositor may find himself helped, or restricted, by the established style of the office, or he may at times be held to strict following of copy. When left to himself he must be guided by the following general principles: I. The comma is used to separate for the eye what is separate in thought. The comma is not intended to break the matter up into lengths suited to the breath of one reading aloud. The comma is not an æsthetic device to improve the appearance of the line. II. The sole purpose of the comma is the unfolding of the sense of the words. III. The comma cannot be correctly used without a thorough understanding of the sense of the words. IV. In case of doubt, omit the comma. And that’s it from Frederick W. Hamilton on the subject of the comma. Next, the semicolon. As an added incentive to purchase The No-Nonsense Proofreading Course (as if any were needed!), I've added three FREE eBooks, totalling more than 340 pages on the subjects of English grammar, punctuation and the importance of the proofreader.

If you've already purchased the course, don't panic! Just drop me a line and I'll send you a link to the free eBooks. |

Details

Testimonials

“I am one of those many fools who paid a huge amount of money for a useless course. This book... has opened so many doors for me. I now look on Mike as my mentor as I embark on a career. Thank you Mike.” Emma Steel, Proofreader and International Structural Editor. “ I thoroughly enjoyed the course and am so glad that I decided to take it... the whole experience was invaluable. My proofreading service is now well established and your course played no small part in getting it off the ground.” Hache L. Jones, Proofreader. “I'd just like to thank you first of all for writing such a great, straight forward eBook, and then going above and beyond what I would even expect as a customer by providing us, completely free of charge, updated versions months later!” Rachel Gee, Trainee Proofreader. “What can I say? Worth every penny and then some! God Bless! This a fabulous course.” Teresa Richardson, Proofreader. “As someone who has effectively been proofreading for thirty years, I found Mike’s No-Nonsense Proofreading Course an invaluable introduction and a very useful practical guide to many aspects of this discipline. I can wholeheartedly recommend it as the ideal starting point, and much more besides.” Jeremy Meehan, Proofreader. Blog AuthorMy name's Mike Sellars and I'm an experienced proofreader and the author of The No-Nonsense Proofreading Course. Click here to find out more about me. The No-Nonsense Proofreading CourseA Fraction of the Cost of Other Proofreading Courses NOTE: Stock is currently limited to 10 per day, so we can continue to deliver exceptional after-sales service, answer queries and provide open-door support. Credit card and PayPal payments accepted. “As someone who has been proofreading for 30 years, I found Mike’s course an invaluable introduction and a very useful practical guide to many aspects of the discipline. I can wholeheartedly recommend it.” Jeremy Meehan, Proofreader. Still want to find out more? Click here. Proofreading Categories

All

Proofreading Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed